Health Risks

Social determinants of health: non-medical factors that influence health outcomes. These include income, education, and healthcare resources (World Health Organization, n.d.)

Climate change poses a multitude of severe health risks to Canada’s Indigenous population. Indigenous Peoples in Canada tend to live in areas that are heavily impacted by climate change such as coastal and northern regions of Canada (Furgal et al., 2002). Indigenous Peoples already experience health inequity in Canada and have adverse effects from a lack of social determinants of positive health (NCCIH, 2022).

Examples of these social determinants of health include Indigenous People’s lower socio-economic status, social marginalization, and lack of access to healthcare. As social determinants of health, these factors multiply the health risks of Indigenous populations (NCCIH, 2022).

Evidence shows a link between the effects of climate change, such as higher temperatures that lead to lower sea ice levels, to impacts on Indigenous People’s health. In Nunavik, Quebec, elders reported increased respiratory stress due to increased summer temperatures (Furgal & Seguin, 2006). Changing weather patterns also impact the migration and patterns of insects such as mosquitoes and bees. These changes and the overall increase in biting insects in Northern communities have led to a fear of a rise in disease from such insects (NCCIH, 2022). These are just a few of the ways climate change is already affecting Indigenous communities.

Spotlight : Sea Ice

As climate change leads to warmer temperatures, it results in a decrease in sea ice that is important to Indigenous lives and cultures. As sea ice is crucial to traditional Indigenous ways of transportation, the loss of sea ice also results in the loss of freedom of movement for Indigenous Peoples (Vogel & Bullock, 2021).

In focus groups of Indigenous people living in Nain, a community in North-East Labrador that is 91% Aboriginal, residents described a positive link between sea ice travel and their health. As sea ice melts, walking or sledding on sea ice becomes more dangerous and even lethal as the risk of frostbite, hypothermia, and drowning increases (Durkalec et al., 2015).

Sea ice: ice that forms from frozen seawater and floats on the surface of a body of water. Scott & Hansen, 2016).

Melting sea ice in the Canadian Arctic. Photo credit: (Goldman, 2017)

The negative effects of climate change on sea ice are already becoming apparent. An Indigenous man in Nain

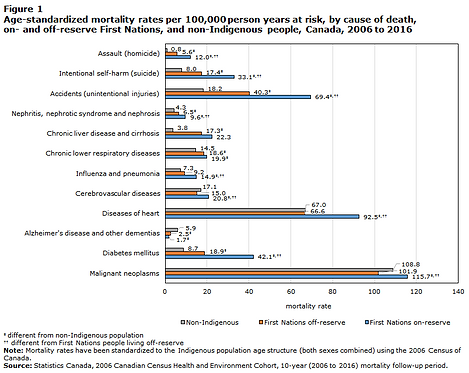

Graph showing mortality rates of Indigenous Peoples, off-reserve First Nations, and Non-Indigenous Canadians from 2006-2016. Photo credit: (Statistics Canada, 2021).

said the ice on the route where he used to collect wood had thinned out and two people had died after falling through the ice (Durkalec et al., 2015). This risk is especially concerning as the rate of unintentional injuries for Inuit communities in Canada is more than four times higher than Canada’s overall rate (Lougheed, 2010). The rate of drowning for Indigenous-Canadians is also six times more than the rate for non-Indigenous Canadians (Canadian Red Cross, 2006). Indigenous-Canadian’s rate of snowmobile accidents is also eight times more than that for non-Indigenous Canadians (Health Canada, 2001). This risk leads to Indigenous Peoples having increasing stress over their safety and the safety of their loved ones.

This phenomenon will also make routes that Indigenous peoples rely on to access natural food resources and culturally significant sites unsafe (Durkalec et al., 2015). While imported foods could be proposed as a solution to decreased natural resources for subsistence, these products are not a sustainable solution as they are expensive due to the high costs of transport and would come with the loss of culturally valued food (Ford et al., 2019).

As seen in the graph to the upper-left, Indigenous Peoples in Canada have significantly higher rates of mortality from certain causes than non-Indigenous Canadians. These causes include death by accident and various health-related causes of death such as influenza and heart disease. As climate change accelerates the risk of accidental death and poor diets from environmental changes, Indigenous Canadians may face disproportionate dangers of climate change in Canada.

Spotlight: Food Insecurity

The First Nations Food, Nutrition and Environment Study (FNFNES), a study that researched the nutrition of Indigenous Peoples across Canada from 2008-2018, reported that 24-60% of Indigenous Peoples in Canada experience food insecurity (“FNFNES”, 2018). Food insecurity is also a risk of climate change as sparse and vulnerable transportation routes in Northern communities are blockaded or otherwise disrupted by extreme and unpredictable weather patterns (Vogel & Bullock, 2021).

An instance of climate-induced food insecurity occurred in the largely Indigenous community of Churchill, Manitoba in 2019 when flooding disrupted the rail tracks surrounding the area and the town was transformed into a fly-in or port access-only community as flooding disrupted the rail tracks surrounding the area. As a result, the price of necessities such as food, bottled water, and other household supplies tripled (CBC News, 2017).

The rapid onset of climate change also brings health risks to Indigenous Peoples in the form of food insecurity. The accessibility and affordability of food in Indigenous communities are poor. Forced assimilation into Western lifestyles has led to Indigenous populations having high rates of certain health issues such as nutritional deficits, diabetes, cancers, and respiratory illness (Furgal et al., 2002).

Food insecurity: the inability or uncertainty that one can access adequate food needed to have a healthy life (Health Canada, n.d.).

Works Cited : Health Risks

-

Amber, C., Agrawal, S., & Zoe, C. (2023). Just transition in the northwest territories: Insights and values from indigenous and non-indigenous northerners. Heliyon, 9(8), e18837–e18837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e18837

-

CBC News. (2017, June 9). Train to Churchill suspended after 'catastrophic' flood damage to track. Canadian Broadcast Corporation. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/manitoba-churchill-rail-service-1.4154221

-

Cross, C. R. (2006). Drownings and Other Water-Related Injuries in Canada, 1991–2000. Module 2: Ice and Cold Water. Canadian Red Cross.

-

Chan, L., Batal, M., Sadik, T., Tikhonov, C., Schwartz, H., Fediuk, K., Ing, A., Marushka, L., Lindhorst, K., Barwin, L., Odele, V., Berti, P., Singh, K., & Receveur, O. (2021).“FNFNES Summary of Findings and Recommendations. Comprehensive Technical Report - Supplemental Data”. (2018). Assembly of First Nations, University of Ottawa, Université de Montréal.

-

Durkalec, A., Furgal, C., Skinner, M. W., & Sheldon, T. (2015). Climate change influences on environment as a determinant of Indigenous health: Relationships to place, sea ice, and health in an Inuit community. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 136–137, 17–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.04.026

-

Ford, J., Clark, D., & Naylor, A. (2019). Food insecurity in Nunavut: Are we going from bad to worse? Canadian Medical Association Journal, 191(20), 550–551.

-

Furgal, C., Martin, D., & Gosselin, P. (2002). Climate Change and Health in Nunavik and Labrador: Lessons from Inuit Knowledge. Nunavik Regional Board of Health and Social Services, Nunavik Nutrition and Health Committee, and Labrador Inuit Association, funded by the Climate Change Action Fund.

-

Furgal, C., & Seguin, J. (2006). Climate Change, Health, and Vulnerability in Canadian Northern Aboriginal Communities. Environmental Health Perspectives, 114(12), 1964–1970. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.8433

-

Health Canada. (n.d.). Household food insecurity in Canada: Overview. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/food-nutrition-surveillance/health-nutrition-surveys/canadian-community-health-survey-cchs/household-food-insecurity-canada-overview.html

-

Health Canada. (2001). Unintentional and intentional injury profile for Aboriginal people in Canada: 1990–1999. Government of Canada. https://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/99966/publication.html

-

Lougheed, M. (2010). Health Indicators of Inuit Nunangat within the Canadian Context. Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. https://policycommons.net/artifacts/1818816/health-indicators-of-inuit-nunangat-within-the-canadian-context/2556277/ on 13 Nov 2023. CID: 20.500.12592/d8j05g.

-

National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health (NCCIH). (2022). Climate Change and Indigenous People’s Health in Canada. (Reprinted with permission from P. Berry & R. Schnitter [eds.], Health of Canadians in a changing climate: Advancing our knowledge for action [Chapter 2]. Government of Canada).

-

Scott, M., & Hansen, K. (2016, September 16). Sea Ice. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/features/SeaIce

-

Vogel, B., & Bullock, R. C. L. (2021). Institutions, indigenous peoples, and climate change adaptation in the Canadian Arctic. GeoJournal, 86(6), 2555–2572. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-020-10212-5

-

World Health Organization. (n.d.). Social determinants of health. https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1

Works Cited (Photos) : Health Risks

-

Goldman, David. (2017). Sea Ice [Photo].

-

Statistics Canada (2021). Mortality among First Nations people, 2006 to 2016 [Graph].